In 2004, the Indian government reduced the long-term capital gains (LTCG) tax rate to 0% and the short-term capital gains (STCG) tax rate to 10%1 on listed equities. By offering favourable tax treatment on capital gains on listed equities, the government sought to attract both domestic and foreign investors. The government introduced the securities transaction tax (STT) in lieu of the capital gains tax reduction.

Since 2004, investors in listed Indian stocks have enjoyed a highly preferential tax treatment compared to any other asset class. Low tax rates and high equity returns have resulted in a strong growth in the equity investor base in India. The number of demat accounts has increased from ~7 million in 2004 to 171 million in August 2024. Investors had become so used to paying zero tax on LTCG that the increase in tax rate to a mere 10% in 2018 was a source of heartburn. Increase in LTCG to 12.5% and STCG to 20% this year further enraged the investor community.

This outrage was largely misplaced considering that capital gains tax rates in India are still low compared to many other large economies. India is now the 5th largest economy and the 4th by listed stock market capitalization. India’s capital markets are fairly vibrant with a large number of listed companies/sectors for investors to choose from. Initially dominated by a few large players, the market has now diversified, with a broader base of investors, including retail investors, domestic institutional investors (DIIs), and foreign institutional investors (FIIs). The pendulum has swung so far that the government and SEBI is now forced to take measures to reduce the heightened activity seen in some parts of the market (derivatives, SME IPOs).

As such, there isn’t a strong reason to continue to retain the tax advantages that were earlier being provided to attract equity investors. It is natural that as a market matures, the government will reduce the tax subsidies being provided to the market participants. Perennially low taxation on equity is unfair to other asset classes like FDs, debt, real estate, etc.

However, there has been one bizarre and under-discussed change in equity taxation over the past few years. This has to do with how corporate payouts, in the form of dividends and buybacks, are taxed. We believe this change has more negative consequences for equity investors in India compared to the hikes in LTCG/STCG taxes.

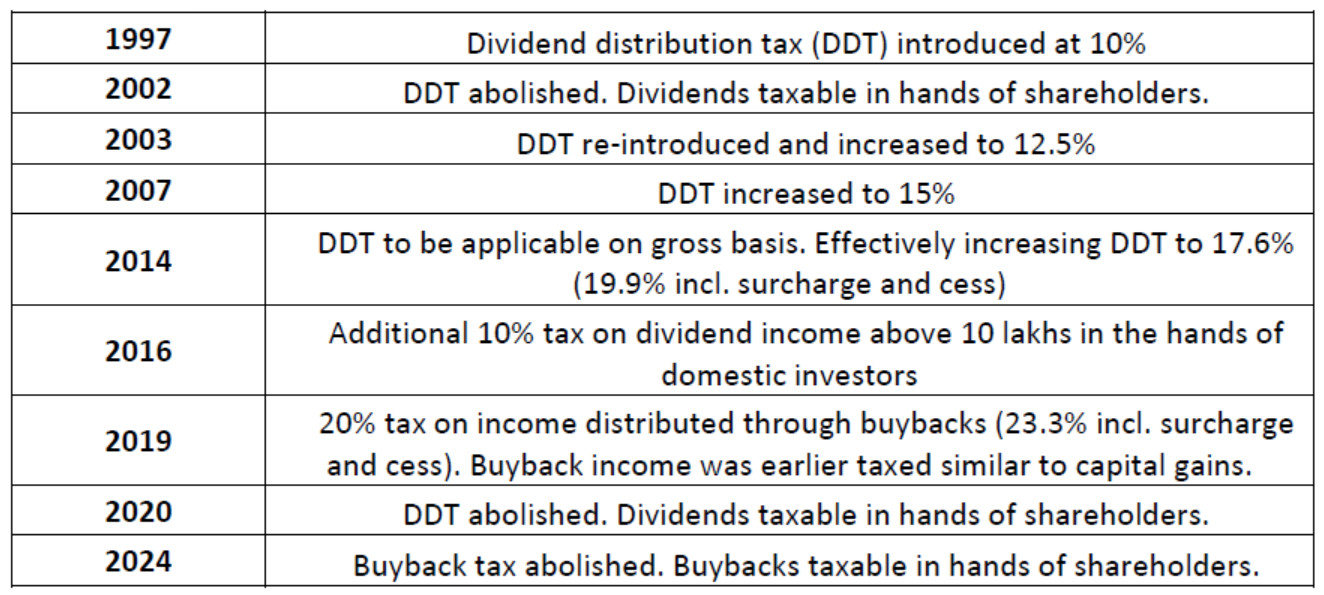

Till a few years back, both dividends and buybacks were taxed at relatively low rates. Till 2014, dividends were taxed at less than 20% and income from buybacks was taxed similar to LTCG/STCG (0%/15%). Over time, taxes on dividends and buybacks have gradually increased, and now both are treated as income in the hands of shareholders and taxed at the marginal rate.

For individual Promoters of listed companies and HNI investors, the effective tax rate on these distributions is ~36% including surcharge and cess. In a matter of 6 years, tax on income from buybacks has increased from 0% to 36% for them. This is a far more material change than the LTCG/STCG tax increases.

While the earlier 0% tax was extremely low, individual Promoters in India are now taxed at rates higher than those paid by any billionaire in the US on buyback income. For instance, long-term capital gains from buybacks are taxed at 20% at the federal level in the US for the highest earners. Some states impose additional taxes, ranging from 0% to 13.3%. The richest person in the US operating out of the most tax-inefficient jurisdiction would still pay a lower tax rate (33.3%) on buyback income than the average Indian Promoter. The differential is even higher given that India, unlike other countries, taxes the entire buyback proceeds and not just the gains. So, an investor can end up footing a large tax bill even without making any profits from the buyback.

We believe the increase in the taxation on corporate payouts through dividends and buybacks will have second-order consequences that will negatively impact all shareholders (and not just HNIs).

- The high tax liability on dividends and buybacks may result in a reduction in payout ratios as Promoters look to minimize their tax liability. Many companies will choose to hoard excess cash rather than distribute it to shareholders.

- Some companies may use the excess cash for unrelated ventures or acquisitions without significant economic rationale. The tax disincentive may encourage empire building by companies.

- Some unethical promoters may use creative ways to access the excess cash to avoid the tax liability, like selling a 100% owned company at an obscene price to the cash rich business – pay only 12.5% on LTCG rather than 36%. Few may route lavish personal expenses and investments through corporate balance sheets rather than from own pocket – like private jets and expensive art purchases. This will hurt minority shareholders.

- In addition to the above shareholder unfriendly actions, the tax increase reduces post-tax returns for investors. This should in the long run result in lower valuations for Indian businesses as a larger part of the value is being shared with the government.

Despite the far larger increase in taxes on corporate payouts and the negative second order consequences, investor attention seems to have been largely focused on the LTCG/STCG tax increases. This might be because the effect of LTCG/STCG taxes is immediate and directly visible while that of dividend/buyback taxes may not be as immediate (no tax liability if company stops dividends or buybacks). Mutual Funds and investors in lower tax brackets may also not experience a direct increase in tax liability from these measures. Some investors may even believe that, since dividends/buybacks account for a smaller part of equity returns in the short term2, higher taxes on them are less consequential than capital gains taxes. That would be flawed logic.

The intrinsic value of a business is determined by the cash flows it generates and distributes to shareholders. If these payouts are now heavily taxed, it effectively reduces the value of the business. Even short-term investors who primarily rely on capital gains rather than dividends or buybacks would be adversely affected if higher taxes on payouts lead to a decline in the business’s value, resulting in reduced capital gains. The unintended consequences mentioned above, along with the decline in intrinsic value, also indirectly impact mutual funds and smaller investors in lower tax brackets.

On the whole, the high taxes on corporate payouts place an invisible but significant burden on all categories of equity investors in India. In the long run, this could lead to adverse changes in corporate payout policies and lower equity valuations.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1STCG tax rate was increased to 15% in 2008

2As the economy and businesses mature, corporate payouts would normally have started to become a larger component of equity returns similar to developed markets. The higher taxes now make that shift uncertain.