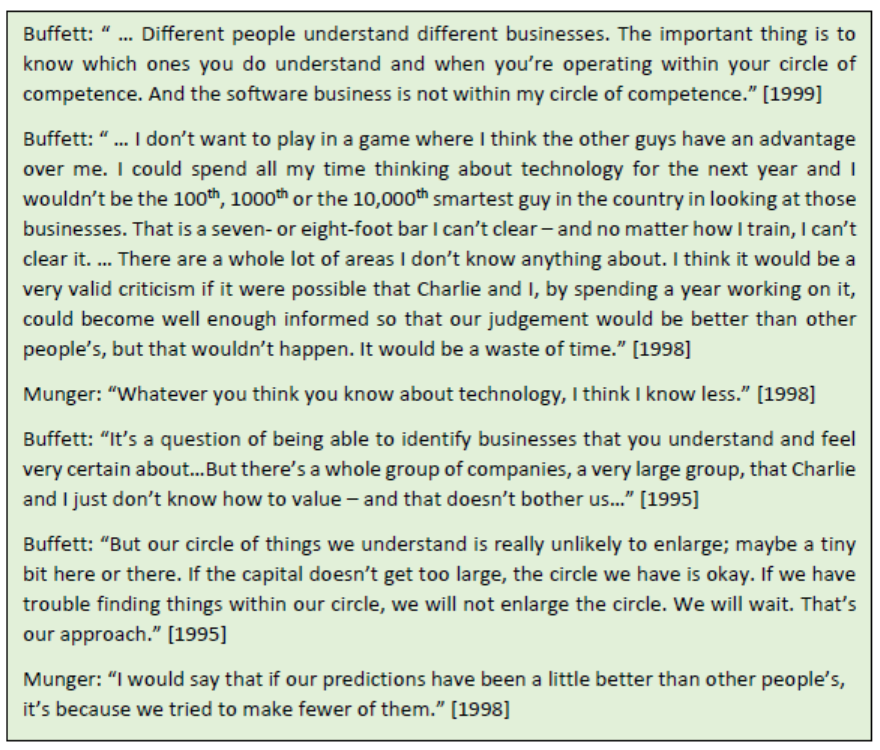

In the late 1990s, Buffett and Munger faced a number of questions from shareholders regarding the lack of high-tech stocks in Berkshire’s portfolio. This was during the dot-com boom, when tech stocks surged, while Berkshire’s performance lagged the overall market. Below are some excerpts from Buffett and Munger’s responses1 to these questions.

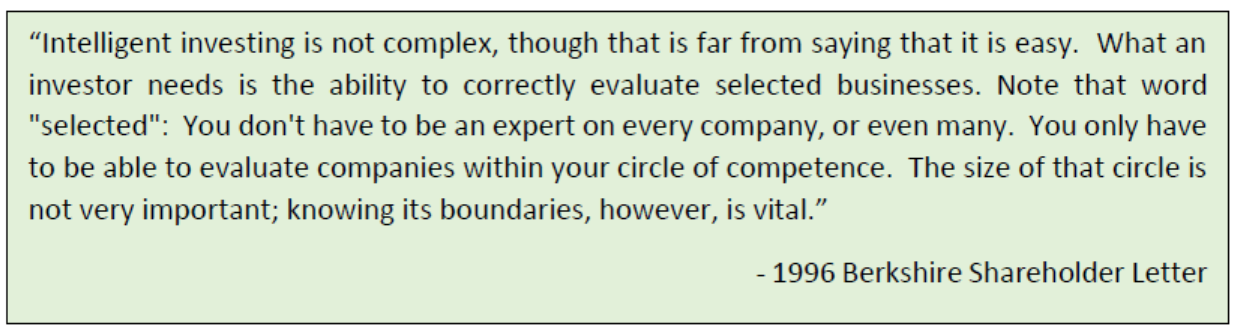

Berkshire avoided tech stocks because Buffett and Munger considered them outside their circle of competence. They doubted that even a considerable effort to studying the industry would materially improve their ability to evaluate these businesses, so they passed. This aspect of knowing and staying within our boundaries is an important guiding principle for successful long-term investing.

New investors are especially likely to ignore, or unintentionally violate, this principle. Many beginners embark on their investment journeys eager to ride every promising wave that comes their way, unaware of their circle of competence and the limits of its boundaries.

Pitfalls of Investing Outside Our Circle of Competence

Investing outside the circle of competence carries significant risks. In territories where our understanding is shallow, our confidence can easily be shaken by short-term negative events or shifts in market perception. This makes it difficult to hold a stock for the long-term. Over the long-term, there will be lot of new information that we will keep receiving on our investment – some of it relevant, much of it noise. We can only do a good job of separating signal from noise if the investment is within our circle of competence.

In 2019, we invested in a leading Indian airline – Interglobe Aviation (Indigo)2. The thesis was simple: secular growth in domestic air travel, Indigo was the most efficient operator, plus a more favourable supply-demand balance after a major competitor’s collapse – all of these should favour IndiGo.

Yet, the company soon began to post disappointing results, even in that benign competitive landscape. Management blamed excess headcount, unexpected maintenance costs, and accounting-rule changes—factors we neither anticipated nor fully understood. We realized that our understanding of Indigo’s business was quite weak. We exited the stock at a loss when Covid hit, as we believed the airline industry would be badly affected. Indigo’s subsequent financial performance further confirmed our limited understanding of the business. Not only did Indigo recoup its Covid-period losses, but it is now 3x more profitable than its pre-Covid highs. The stock is up 5x from our exit price.

The episode is a good reminder that long-term investing works only inside one’s circle of competence. Staying within the boundaries of what we know well improves the quality of decision-making. When we grasp an industry’s economics and nuances, we can assess risks accurately, ignore the noise, and hold – or even add – through turbulence. Fortunately, in other holdings that fell inside our circle, we did just that and benefitted from subsequent strong business performance.

Overestimating Our Circle of Competence

Buffett and Munger were reluctant to even devote too much energy to studying the tech sector because the inherent complexity of the industry made it a pointless exercise. In today’s digital age, this behaviour would be considered archaic. Understanding a sector these days requires only reading a few earnings call transcripts, using a few ChatGPT prompts, watching YouTube explainer videos and conducting some cursory historical financial analysis. There is no industry in which the modern, tech-savvy investor can’t gain competence with just a few weeks of effort. No industry is unknowable. Investors who altogether avoid investing in certain sectors are considered lazy or too rigid (they are “NGMI”).

On the contrary, with the democratization of information, having access to data and surface-level insights no longer provides investors with a meaningful edge. The sheer volume of readily available resources means that merely being informed isn’t enough. Investors need a deeper understanding and more nuanced analysis to truly stand out. A business or industry is within our circle of competence only if we have a material edge in understanding it vs other market participants. That is more difficult to achieve today than it was when Buffett and Munger were wondering about their competence to invest in the tech sector. Arguably, then, most investors’ true circles of competence are narrower now than they were decades ago.

Overestimating the boundaries of our circle of competence is a bigger problem than having a small circle and knowing it. An investor operating within their small circle can choose to patiently wait for investment opportunities to emerge and only swing his bat when the right opportunity arrives. An investor unaware of the true boundaries of his circle will swing a lot more at balls that should be left alone. A false sense of competence can lead to overconfidence, poor decision-making, and investments driven by speculation rather than informed analysis.

Mapping – and Widening – Your Circle of Competence

Understanding and respecting your boundaries is an essential skill required for successful long-term investing. By systematically assessing your strengths and acknowledging your limitations, you can develop a disciplined approach that minimizes risks and leads to positive outcomes. Over time, this process allows you to expand your circle of competence, make more informed decisions, and build greater confidence in your investment choices.

Investors may find some of the below points useful to understand and expand their boundaries over time.

- Assess your knowledge: Reflect on industries, sectors, and business models you’re already familiar with—be it technology, FMCG, banks/NBFCs, or others.

- Limit your focus: Instead of trying to analyze 100s of companies, limit yourself to a manageable number within your competence.

- Be honest about gaps: Admit when you don’t understand a company or sector and avoid investing in areas outside your expertise. When in doubt, start with smaller position sizes and seek a higher margin of safety.

- Start with simple: Begin with simpler industries that have fewer moving parts (like consumer goods) before venturing into complex areas (like deep tech, pharma).

- Learn continuously: As you gain more knowledge, gradually expand your circle. Learn from other investors and industry experts to fill in the gaps in your knowledge. Use your and others’ mistakes to improve your understanding of what you do know and what you can know.

Charlie Munger referred to three types of investment decisions – yes, no and too hard. The “Too Hard” bucket referred to those investments that were deemed to be outside their circle of competence. While we should continuously strive to widen our circle of competence, we should also embrace the “Too Hard” pile. We should try to improve our understanding of what we don’t know and what we cannot know. By acknowledging what is beyond our comprehension or capability, we safeguard ourselves against making ill-informed, risky decisions.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Sourced from Buffett & Munger Unscripted by Alex W. Morris – a fantastic book that covers Buffett and Munger’s answers to the questions at Berkshire’s AGMs between 1994-2024.

2 We had earlier written about our Indigo investment in Our Worst Investments (So Far)