While there has been a rise in market valuations in recent times, it has been exacerbated by the rise of superficial methods of justifying these valuations. Increasingly, investors, including seasoned professionals, are no longer valuing businesses using first principles. They are relying on second-order pricing constructs where price is justified by reference to other prices rather than to business economics.

The first principle of valuation is that the value of a business is the cash it will generate for its owners over its life, discounted for time and risk. First principles are the most basic and undeniable truths but in the stock market they seem to be easily forgotten. First-principles thinking forces discipline. It anchors expectations to reality:

- What is the sustainable free cash flow of the business?

- How long can it compound? What risks could impair that compounding?

- What reinvestment opportunities exist?

- What competitive risks could impact margins?

Below, we discuss two popular second-order pricing constructs that have replaced this discipline.

The Greater-Fool Theory

Valuation for many investors, including professional investors has quietly morphed into a second-order guessing game: What multiple will someone else be willing to pay in the future?

Keynes wrote about this in 1936 in his book “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money” but it is as relevant today as it was then.

If the only justification for owning a stock is that someone else may assign it a higher multiple later, then the investor is no longer underwriting a business. They are underwriting market psychology.

This logic can be aptly described as “greater fool theory”. Although this logic has become mainstream, it is rarely described so bluntly. Instead, it is disguised in professional jargon like “multiple re-rating potential” or “valuation headroom”. Investors justify these inflated prices by claiming the company deserves a “structural premium” because it fits a trendy narrative, whether as a “consumer brand”, a “defense proxy”, a “platform business”, or a part of the “China + 1” manufacturing shift.

But at its core, the bet is the same: “I am comfortable paying this price because I believe someone else will pay more”. Not because the business will generate cash flows that justify it, but because the market’s future perception might. This is speculation, even when practiced by professionals.

Relative Valuation

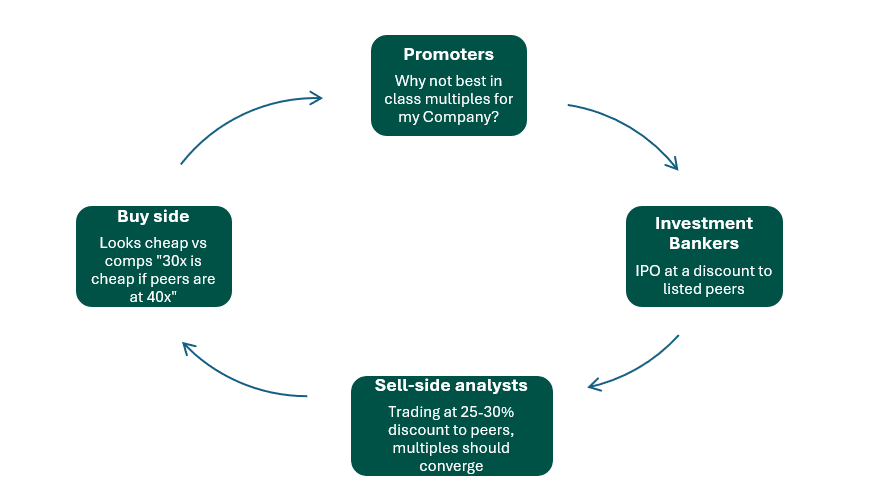

Promoters, investment bankers, and sell-side analysts all participate synchronously along with investors in reinforcing and normalizing elevated multiples through the lens of relative valuation.

It is common to hear promoters ask, ‘Why is my company valued at 35x when Company X trades at 50x?’1 This stems from a healthy, competitive desire to see their hard work recognized by the market. However, this often turns valuation into a target to be reached through comparison, rather than an independent assessment based on the company’s unique characteristics.

Investment bankers often reinforce the Promoter’s logic in pricing the IPOs. Valuation is framed as “at a discount to listed peers”, or “comparable to global benchmarks”.

Sell-side research analysts, who should anchor to fundamentals, often adopt the same framework. Sell-side models are numerically detailed. But terminal value is frequently anchored to peer multiples. This assumes that peer multiples are correct and that convergence is inevitable.

Relative valuation offers a sense of security to all the participants as promoters feel justified, bankers feel validated, analysts feel career-safe and investors feel rational.

Why This Works (Until It Doesn’t)

Second order pricing constructs thrive in environments where liquidity is abundant, recent returns dominate memory, time horizons are short and career risk outweighs absolute risk.

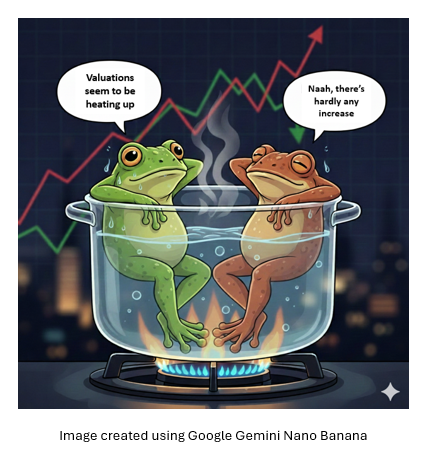

As long as flows remain strong, the system reinforces itself. Higher valuations validate prior decisions, which then become the benchmark for the next trade. What makes this shift especially dangerous is that it happens gradually. Valuation standards are not reset overnight. They drift quietly and persistently, until what once felt extreme now feels normal. This is the boiling frog syndrome: a 40x earnings multiple is no longer “expensive”, it is the new 20x.

In such environments – price discovery weakens, capital misallocates, risk is systematically underpriced and drawdowns become sharper.

But these constructs have a hidden fragility because there is no anchor. When sentiment turns due to a modest growth disappointment, a margin squeeze, a liquidity shift, or simply the passage of time, then second-order pricing constructs offer no downside protection. What once felt like “the new normal”, suddenly feels indefensible.

As Howard Marks wrote in his November 2022 memo (What Really Matters):

“Wanting to own a business for its commercial merit and long-term earnings potential is a good reason to be a stockholder, and if these expectations are borne out, a good reason to believe the stock price will rise. In the absence of that, buying in the hope of appreciation merely amounts to trying to guess which industries and companies investors will favor in the future. Ben Graham famously said, “In the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.” While none of this is easy, as Charlie Munger once told me, carefully weighing long-term merit should produce better results than trying to guess at short-term swings in popularity.”

Returns earned through the playing out of pricing constructs are the most reversible form of returns. When the market stops being a “voting machine” and starts being a “weighing machine”, the lack of fundamental weight becomes painfully apparent.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Few years back, we attended a dairy company’s analyst meet where the Promoter made a passionate presentation demanding to be valued similar to FMCG businesses. It subsequently reported a large loss after writing off a significant portion of its inventory.