“Show me the money!” – Jerry Maguire

With rising interest rates and tightening liquidity, the environment is becoming tougher for many dodgy businesses. These are companies that use all sorts of accounting shenanigans to report accounting profits even though the business truly does not make any money. Such frauds thrive in bull markets when investors focus primarily on accounting profits, and value businesses using earnings-based metrics like P/E or EV/EBITDA. The more the company is able to inflate its profits, the higher it gets valued. It is difficult for investors to ignore companies that are consistently reporting high ROEs and strong earnings growth.

There are two main methods that companies use to inflate accounting profits – (1) Exaggerating Revenue (2) Under-reporting Expenses.

Enron used creative mark-to-market accounting to recognize upfront the projected revenue over the life of the asset, based on its own assumptions. Worldcom management overstated profits by US $3.8 billion by capitalizing line costs as assets before being caught by an internal audit. AOL capitalized its advertising and customer acquisition costs to report profits instead of large losses.

A large number of companies in India have also been found cooking their books. Satyam used over 7000 fake bills to inflate revenues by 25% and profits by 10x. In 2019, Manpasand Beverages management was arrested in a fake GST invoice fraud. The company had raised 500 crs at a billion $ valuation just a few years before that. In our diligence, we found a prominent small-cap pharma company paying its senior management salaries in cash1 – this allowed it to raise equity capital at high valuations as investors (including Private Equity funds) were attracted to the inflated profitability. Many other companies like DHFL, Talwalkar’s, Ricoh India, 8K Miles, Eros, etc. have suddenly gone bust despite reporting bumper profits in prior periods.

Missing Cash Flows

One of the common traits of the companies mentioned earlier (apart from cooking of books) is that none of them generated cash flows2. While they reported super-normal profits in many cases, these businesses were constantly raising debt or equity to survive. We believe that this is an important characteristic of many fraudulent businesses and one that can be used by investors to avoid landmines such as the ones mentioned above.

While earnings manipulation is easy, it is not cheap. To report fake profits, companies need to spend real cash. Fake profits too require payment of real taxes to the government3. Similarly, fake revenues lead to leakages such as GST payments, and commission payments to agents supplying fake bills.

Expenses whether paid in cash or through other entities to inflate the P&L profits still need to be paid from the promoter’s pocket. All of these costs can add up to become a sizable amount (it is an upfront investment from the fraudster’s perspective).

These costs are a problem. It creates a big mismatch between the tons of cash that the business would have generated if the profits were real, versus the actual cash outflow happening to run the fraud. This is why the P&L and the Cash Flow statement of a fraudulent business can paint a very different picture.

Most often, the promoters defend the negative cash flows by blaming it on the high growth trajectory of the business. This typically manifests in two ways in the reported financials of the company –

1. High Working Capital/Other Current Assets

The company can report a large and growing amount of capital stuck in working capital. High receivables and inventories are a common feature in such companies. High loans and advances paid to suppliers are also justified for growth. This typically results in low or negative cash flow from operations.

2. Large capex/acquisitions

Some companies will have large capex and acquisition related outflows which will result in negative cash flow from investing. They may claim that these investments are necessary for the long-term growth of the company and will deliver positive cash flow in the future.

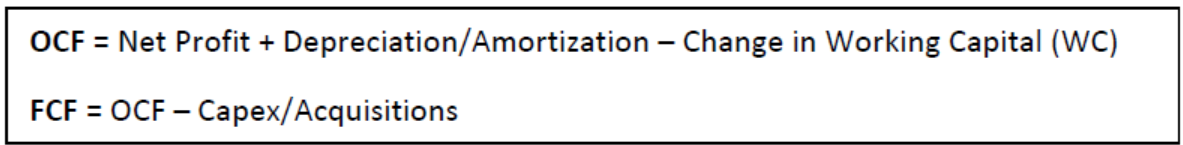

Free Cash Flow (FCF) thumps Operating Cash Flow (OCF)

We can identify many instances of accounting fraud by studying the OCF and FCF in detail.

A company struggling to generate +ve OCF over a long period despite reporting healthy P&L profits, is probably hiding some skeletons in its cupboards. Analysts now track this metric closely and managements are likely to be questioned if there is a divergence between OCF and accounting cash profits. This has resulted in most fraudulent promoters striving to show a +ve and rising OCF. Companies have several levers that they can use to manage OCF – delaying vendor payments, receivables factoring, discounts on cash advances for future sales, mis-classifying OCF as investing cash flow or financing cash flow, etc. A large Indian conglomerate is known for its expertise in using off-balance sheet financing to show a healthy OCF.

Persistent -ve FCF due to capex does not yet draw as much analyst attention as -ve OCF. Large capex announcements are viewed positively by the investor community, as an indicator of strong underlying business demand and eventual future growth. Analysts will often project future revenues/profits based on projected capacity. However, it is difficult to independently verify the genuineness of the capex number. For example, an analyst is unlikely to know whether the real cost of a manufacturing plant is 100 crs or 200 crs or whether the actual capacity of a plant is X or 5X. Analysts are largely dependent on management guidance in these instances and can be easily misled. The opacity of the capex numbers makes it an easy avenue for fraudsters to siphon out capital without raising any red flags.

We believe that FCF is more useful than OCF to identify frauds as it accounts for capital used for both working capital and capex purposes. This is because fraudsters have become wise to analysts’ focus on OCF and are increasingly using capex for siphoning out capital. It is also easy to spin a positive narrative around large capex, while it is difficult to justify large amounts stuck in working capital. OCF is also easier to manipulate4, whereas manipulating FCF is harder. It is no surprise that most of the large accounting frauds had healthy accounting profits and OCF but weak FCF numbers. As fraudsters become smarter, the relevance of OCF as an accounting fraud detection metric is likely to further decline.

Case Study – TOPO

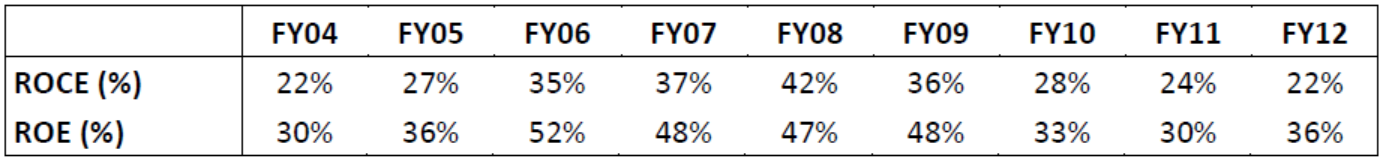

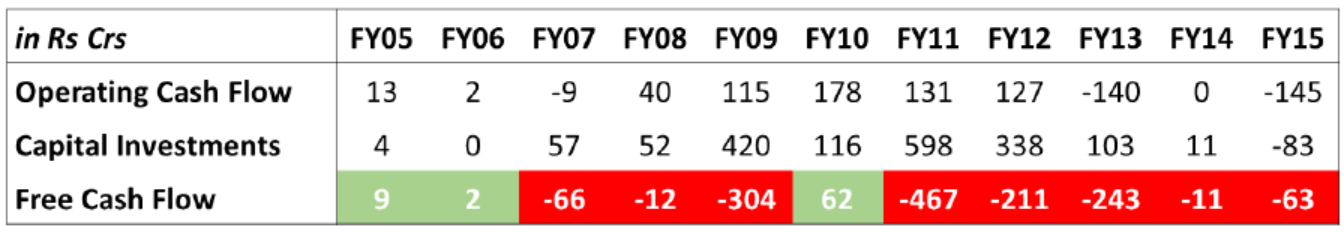

Between FY04-FY12, TOPO reported phenomenal increase in profitability with PAT margins above 20% and ROEs consistently above 30%. Purely on these metrics, TOPO looked like a great business to own.

Over this period, the stock delivered ~50x returns and the company was able to raise 100s of crs of equity and debt capital. However, the profitability soon saw a serious downturn and never recovered.

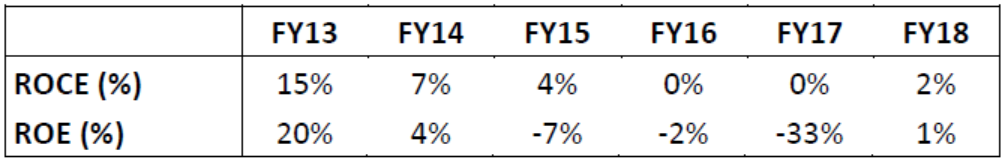

The stock collapsed and even the lenders had to take a large haircut. Was this just a normal business failure or a case of fraud? The cash flow statement provides some clues.

While TOPO was reporting great accounting profits, its FCF was a sea of red with large and increasing losses. TOPO was also able to show reasonably good OCF numbers as most of the fraud was routed through the capex/acquisitions route. An analyst paying attention to the large FCF losses may have been able to avoid the TOPO landmine.

Caveats

Focussing on free cash flows will help investors avoid many investing landmines. But there are always exceptions.

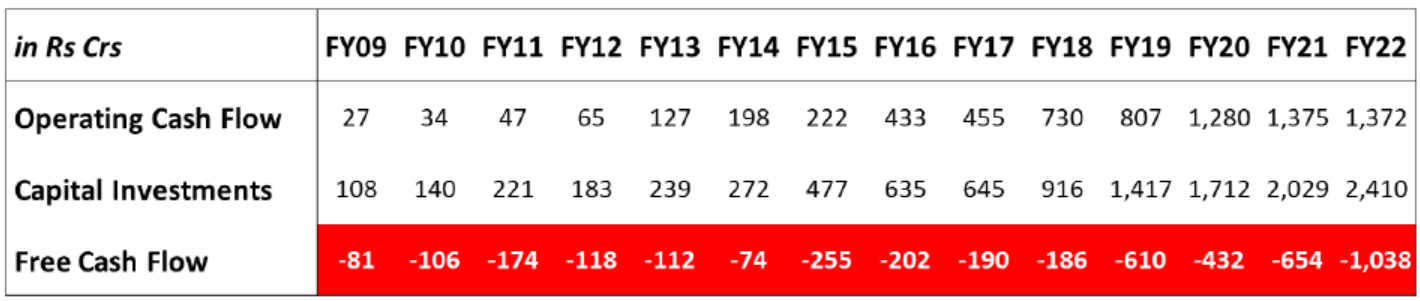

Not all companies that have strong accounting profits and OCF but weak FCF over long periods of time are fraudulent. For some of these companies, there may be genuine business reasons that explain the divergence. Consider the below company. If TOPO’s FCF numbers were bad, this looks like a horror-show.

This is D-Mart. The company’s business strategy to own its stores makes its business model highly capital intensive. Its rapid growth has necessitated large investments for land purchase and store construction. Companies like Wal-Mart and Home Depot had similarly seen long periods of -ve FCF in their growth phase. There will always be such exceptions but it is important to remember that these are rare cases.

Similarly, just because a company is reporting good free cash flows does not mean everything is hunky dory. Some fraudsters have taken the fraud game a notch higher by ensuring that the FCF too looks solid. Such supposedly cash-rich businesses can also be landmines. Professor Sanjay Bakshi had in 20095 written an article, Show Me The Money!, giving examples of companies whose cash balances looked suspect as they were not earning any treasury income and lying idle in some unknown foreign banks. A few years back, an 8 billion $ market cap company reported more than 500 crs as cheques-in-hand (!) and in 0-interest earning current accounts – the stock is down 95% from its peak and the cash has vanished. Cash is king but only if it is real.

(Avoiding Landmines is our series of articles where we highlight (1) tricks that companies use to commit fraud and (2) methods to identify corporate governance issues. In this series, we had earlier written about The Panama Pump, The Markopolos Method and Market Cap Without Human-Cap)

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Double benefit – the company is able to report higher accounting profits and the employees don’t pay taxes on the unaccounted income.

2 Satyam reported positive cash flows by falsifying even cash balances in its financial statements. Post-Satyam, this has become a little difficult as auditors now do independent checks of cash balances.

3 We have seen companies advertise payment of large advance taxes as evidence of their profits being real. We should stay away from such companies as real tax payment is just the cost of running a proper fraud.

4 Twitter thread by Nitin Mangal on how companies manipulate OCF – bit.ly/OCF_Nitin

5 Just a fortnight after the collapse of Satyam